Biggest art theft ever' remains unsolved and is the subject of a documentary on Netflix

More than 30 years later, the theft of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston remains unsolved

It was dawn on March 18, 1990, when two men wearing police uniforms arrived at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States, and told guards on duty that they were investigating disturbances in that area of the American city.

They soon tied the two guards and, for exactly 81 minutes, stole 13 works of art by names like Rembrandt, Vermeer, Degas, Manet and other renowned artists.

More than 30 years later, crime is still considered the greatest art theft in history and remains unsolved.

The total value of the works taken by the criminals, which include paintings, prints and historical artifacts, is estimated at more than half a billion dollars (about R $ 2.8 billion).

The museum still marks the place where the pieces were displayed with empty frames, waiting for their return, and continues to offer a reward of US $ 10 million (about R $ 56 million) for "information that leads to the recovery of all the stolen works. ".

But despite countless theories and suspects, ranging from people with privileged access to the museum to members of the mafia, the investigations have never led to a conclusion about who was to blame or where the works are hidden.

Over the years, this mystery has captivated the American public and has been the subject of several books, podcasts and even chapters of TV series, such as The Simpsons .

Now, the subject has reawakened interest with the premiere this week of the documentary The Greatest Art Theft of All Time , on Netflix. Divided into four episodes and directed by Colin Barnicle, the series explores the details of the theft and the investigation.

The total value of the stolen works, which include paintings, prints and historical artifacts, is valued at more than half a billion dollars

The details of the theft

Many people were still out on the street that morning, returning home after St. Patrick's Day celebrations. Some of these people later said they saw two men in police uniforms in a car parked near a side door of the museum at about 12:30 am.

"Two guards were on duty that night," reports Anthony Amore, the head of security, in an audio deposition released by the museum.

According to Amore, at 1:24 am the robbers, dressed as police officers from the Boston Police Department, arrived at the outer door of the security area where the guards were staying.

"Through the intercom, outside, the thieves said they were responding to a report of disturbance. It seemed plausible. After all, it was St. Patrick's Day night and revelers were still on the street," he recalls.

Contrary to protocol, one of the guards on duty, Richard Abath, opened the door for the alleged policemen, allowing them to enter through the employees' concierge.

"Once inside the museum, they immediately overpowered the guards. They covered their eyes and mouths with duct tape and put them in the basement, away from each other, handcuffed," says Amore.

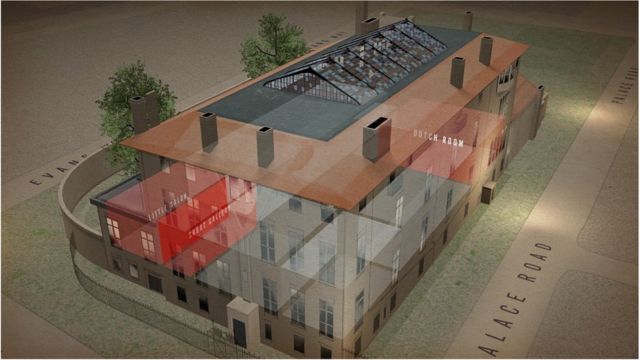

For more than an hour, criminals toured several galleries in the museum, cutting works of art from their frames and scattering broken glass across the floor.

Among the stolen works were valuable paintings, such as Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) and Lady and Knight in Black , both by Rembrandt, and Vermeer's Concerto (1663-1666).

But, according to the head of security, the thieves also left behind rare and very valuable works, while taking other pieces of lesser value, which confuses the investigators. For Amore, the criminals "weren't exactly art experts."

Two men dressed in police uniforms convinced the guards to open the door and entered the museum at dawn

The thieves left at 2:45 am, after making two separate trips to the car carrying the works of art.

"They spent 81 minutes at the museum. Imagine that, an hour and 21 minutes! Most art thefts are quick actions, from five to ten minutes," notes Amore.

The investigation

The guards remained handcuffed until the police arrived at 8:15 am.

A few days later, the FBI (the American federal police) released a sketch and described the suspects as "two white men with dark hair and dark eyes".

Initially, there were suspicions about Abath, the guard who opened the door for criminals, who at the time was 23 years old.

That night, before the theft, he would have opened and closed the museum door quickly, which, for some, could have signaled the thieves.

Another suspicion was that he might have stolen a piece that disappeared from the Blue Room, a gallery where motion detectors only captured his presence during one of the rounds, but not that of the thieves.

In interviews with the American press in later years, Abath admitted that he sometimes arrived at work drunk or after using drugs and that he even let a group of friends enter the museum after closing, which was forbidden.

According to Abath, the main attraction of the job was the free time he had to dedicate himself to what he really liked, which was playing in rock bands.

But he always denied any involvement in the crime, and said that his actions that morning were the result of a lack of proper training. He was never charged.

Theories

There were also suspicions of the involvement of mafia members or local gangs and that the stolen pieces were being transported to other cities through these criminal networks.

Many believed that James "Whitey" Bulger, one of Boston's most powerful mobsters, had some sort of involvement in the crime, but that was never proven, and he was killed in 2018.

Myles Connor Jr, a well-known art thief who had already robbed several museums, was in prison at the time, but some believed he could have organized the crime even from inside the prison.

The criminals toured several galleries of the museum for 81 minutes and took away both valuable works and pieces of lesser value

Another theory was that mobster Robert Donati was planning to exchange the works for the freedom of one of the bosses arrested at the time. Donati was killed in 1991.

Another mobster, Carmello Merlino, reportedly told informants that he planned to recover the stolen pieces and receive the reward. He died in 2005, while serving a prison sentence for an armed robbery unrelated to the crime in the museum.

In 2015, two of his cronies, George Reissfelder and Leonard DiMuzio, came to be identified as the probable criminals. They had died years before, in 1991.

Over the years, several others have been suspected of involvement in the crime, including bank robber Robert Guarente, who died in 2004, Irish criminal Martin Foley, called "The Viper", and gangsters Louis Royce and David Turner.

To this day, however, despite multiple suspicions, no one has ever been arrested and the fate of the stolen works is unknown.

In the more than 30 years since the crime, the authorities involved in the investigation estimate to have received at least 30,000 contacts from people who said they had some clue.

"We still hope that the pieces will be recovered," says Amore, when asking anyone who has a clue to get in touch.

No comments:

Post a Comment