From covid to ebola: where do disease names come from?

In recent years, experts have identified flu outbreaks with letters and numbers, but many find it difficult to remember

When we learn of the emergence of a new disease - as was the case recently with covid-19, we try to learn about the causes, the symptoms and how we can prevent it.

We rarely stop to look at the name of a disease or why they decided to call it a certain way.

However, disease names have enormous political, economic and social weight.

"When a new threat to life arises, the first and most pressing concern is to give it a name," says science journalist Laura Spinney in her book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World ( " Cavaleiro Pálido: the Spanish flu of 1918 and how it changed the world ".

"It is very difficult to talk about something that does not have a name and even more difficult to fight it. After giving a name, you can talk about it, discuss possible solutions, adopt or reject these solutions, convey a public health message and ask that people comply with, "he said.

"I think there is nothing more frightening than something that has no name and you don't know what it is."

However, sometimes, when an infectious disease arises, the authorities rush to name it before they even know all its symptoms and effects. And, occasionally, these names end up being misleading or confusing.

Swine flu caused panic in 2009 and led Egypt to slaughter 300,000 pigs

One example that the expert cited was the pandemic of the so-called swine flu, caused by the H1N1 virus, which appeared in 2009.

"It is likely that it came about with a transmission from pigs to humans, but the reason why it became a dangerous disease is that it was transmitted between humans," he said.

The chosen name had strong consequences: many countries banned pork imports, and in Egypt they made the drastic decision to sacrifice all pigs: about 300,000 animals that were raised mainly by the Copts, a Christian minority.

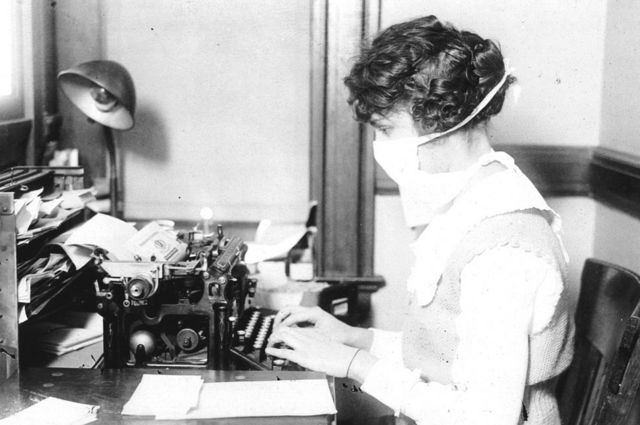

Spanish flu did not appear in Spain

The most famous case of a wrongly named disease was the worst flu outbreak in history, which killed more than 50 million people worldwide in 1918 and 1919.

Even today, a hundred years later, we continue to call it the Spanish flu. However, "there was nothing particularly Spanish about the disease," said Spinney.

"It affected Spain, but it didn't start in Spain, we believe it probably started in the United States, although we're not sure."

"The reason it was called the Spanish flu was because Spain remained neutral during World War I and did not censor its newspapers, as did the United States, the United Kingdom, France and nations at war, which prohibited reporting on the flu so as not to lower the morale of the population ", he explains.

The Spanish press reported flu cases, which were censored in the US and the rest of Europe, and people mistakenly thought the disease had arisen there

"So, when the Spaniards started to report the first cases that arose in Madrid, which occurred several months after the first cases in the United States - something they did not know -, the rest of the world thought that the disease had arisen in Madrid, and they called it the Spanish flu. "

Multiple origins

Despite this error, the truth is that in the past it was very common to name a disease according to the place where it arose - or where it is believed to have arisen.

Linguist Laura Wright listed several examples for the BBC, such as Malta fever, Mediterranean fever or Lyme disease, in reference to the small town in Connecticut, in the United States, where it was first discovered.

According to her, in the distant past, before there were scientists who specialized in viruses and bacteria, diseases also received the names of animals - for example, chicken pox, which in English is called chicken pox , which refers to chicken, or scrofula, which it comes from Latin and means something like "little nut".

Another origin referred to the appearance or attitude of the patients after the infection. For example, smallpox was called small pox in English because of the small marks it leaves on the face.

In modern times, some diseases have also been given names based on who was affected by them. One example is the Legionnaire's disease, which received its name because the first known victims were members of the American Legion who attended a convention at a hotel in 1976.

There are also many diseases and conditions that have been named by scientists who have identified their cause, such as listeriosis (in reference to the English surgeon Joseph Lister), Down syndrome and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (also known as the human version of the disease). Crazy Cow).

Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the UK, and a professor of global health, told the BBC that many experts today would find it tasteless to use his name to identify a fatal disease.

In 1976, Piot was one of the scientists who discovered the Ebola virus, which was named after a remote river near a village in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where hemorrhagic fever was discovered.

Peter Piot was one of the discoverers of the Ebola virus and helped to choose that name, which sought not to stigmatize anyone

According to him, the traditional way of naming diseases by the place where they would have arisen causes a lot of stigma.

"When you identify a disease with the name of a country, it can have a political connotation and also huge consequences: borders are closed, and flights are canceled to that destination. There are huge consequences for the entire economy of the country."

New rules

The World Health Organization (WHO) criticized, for example, the choice of the name Mers (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), whose first outbreak was registered in Saudi Arabia in April 2012.

"We have seen that certain disease names provoke a reaction against members of specific religious or ethnic communities, create unjustified barriers to travel, trade and commerce and cause the unnecessary slaughter of animals for food," the WHO said in a statement.

As a result, new rules were created in 2015 to name diseases and avoid past mistakes.

"The name must not stigmatize or cite specific places, nor animals or human groups. It must avoid alarming words like 'fatal' or 'unknown' and must be neutral," explained Piot.

The WHO also says that the name should be short and descriptive - like that of Sars (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, in the acronym in English).

Covid-19

Covid-19, a disease caused by the new coronavirus (Sars-CoV-2), was named by WHO within the new guidelines. But do you know where that name came from?

The name derives from the words "corona", "virus" and "disease", with 2019 representing the year in which it emerged - the outbreak was reported to WHO on December 31.

"We had to find a name that did not refer to a geographical location, an animal, an individual or a group of people, and that is also pronounceable and related to the disease," explained WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at the time. .

"Having a name is important to prevent the use of other names that may be inaccurate or stigmatizing. It also provides us with a standard to be used in future coronavirus outbreaks."

The delay in announcing the official name, however, can have consequences:

"The danger when you don't have an official name is that people start using terms like 'China virus', and that could create discrimination against certain populations," said Crystal Watson, assistant professor at the Center for Health Security in Johns Hopkins, in the USA.

With social media, unofficial names take hold quickly and are difficult to change, she says.

Name the oxen

Regarding the WHO guidelines, Laura Spinney warns that the adoption of a neutral name, which does not mention the source of contagion and avoids causing fanfare, can be dangerous.

"I think the WHO's intention to avoid stigma and discrimination is good, but in this context a name has to put people on the alert and clarify what are the potential sources of infection that should be avoided," he said.

"Tasteless and forgettable names will not make people aware, because they will not know what we are talking about."

The science journalist points out that sometimes calling things by name can have a positive effect.

Laura Spinney believes that it is important to identify the industries that generate risks to public health due to their bad practices

"Sometimes, naming the origin puts pressure on a sector to prevent the risk from being even greater. For example, 'bird flu' suggests some responsibility for the agricultural sector and the governments that regulate it."

"But if you extract that information from the name, there will be less pressure, and no one will be forced to take charge of it."

But experts agree that, after all, there is no specific person or group that decides the name of a disease: they can be doctors, politicians, bureaucrats or journalists.

"Simply the name that 'catches' is the name that remains," said Spinney.

From a linguistic point of view, Wright believes that the new WHO guidelines have a limited effect.

"The rules assume that there is a power that can control the language, and that does not exist. People are going to call it what they want."

No comments:

Post a Comment