How American city will use marijuana taxes to fund reparations for black residents

Evanston, Illinois, will distribute $ 10 million to black residents over ten years

In a decision announced as historic, the American city of Evanston, in the state of Illinois, this month became the first in the United States to offer financial redress to black residents, in a program that could serve as a model for such initiatives elsewhere. from the country.

While other American cities and states have already approved the creation of commissions to develop redress proposals for descendants of enslaved people and victims of policies of segregation and racism, Evanston, in the Chicago metropolitan area, is the first to allocate funds for cash refunds.

A resolution passed in March by the City Council determined the distribution of the first resources of a reparations fund created in 2019 and which foresees a total of US $ 10 million (about R $ 57 million) over ten years.

In this first phase, the focus will be on housing, with US $ 400 thousand (about R $ 2.28 million) distributed to 16 black residents whose families were affected by racist housing policies in force in the city between 1919 and 1969 or who suffered discrimination in that sector in later years.

Although it also accepts donations, the initiative will be financed mainly with taxes on the sale of marijuana for recreational use, which was legalized in the state last year.

"This is poetic justice," Ron Daniels, one of the leaders of the National African American Reparations Commission, or Naarc, tells BBC News Brasil.

"Because the war on drugs, including marijuana, targeted the black population," says Daniels, whose organization participated in drafting the plan.

Black Americans represent 13% of the population, but hold only 2.6% of the country's wealth

Marijuana legalization is advancing in the United States, where 36 of the 50 states allow medical use and 15 also recreational use. Historical data show the negative impact that criminalization has had on black communities.

Kamm Howard, one of the leaders of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, or N'Cobra, which also helped to design the Evanston plan, cites studies according to which, although blacks and whites use marijuana in the same proportion, the likelihood of black users being arrested is higher.

"(Black residents) were more policed and more incarcerated and suffered all the losses associated with having a police record," says Howard to BBC News Brasil.

Economic inequalities

The announcement about the program in Evanston comes at a time when the debate on reparations is gaining momentum in the country.

Interest, which had already been growing, increased even more last year, amid protests against racial injustice and in the face of the covid-19 pandemic and the economic crisis, which disproportionately affected the black population and made racial disparities clear.

But the idea that the government should pay financial compensation to the black population for the damage caused by slavery has been debated in the United States since at least the end of the Civil War in 1865, in some periods with greater emphasis than in others.

The cumulative impact of two and a half centuries of slavery and the decades of segregation, racial terror and discriminatory policies that followed is visible in the inequalities in income and wealth that still persist. Although black Americans currently make up 13% of the population, they hold only 2.6% of the country's wealth.

While white people were able to buy land and thus leave it as an inheritance to their descendants, the enslaved black population did not have that right. Even after abolition, several laws prevented or made it difficult for black Americans to vote, study, have access to good jobs and finance or acquire property.

In Evanston, where about 16% of the 75,000 inhabitants are black, the creators of the reparations plan decided to focus initially on housing after a detailed report on the city's historic black population restrictions in this sector and after consultation with the community.

"The goal is to try to reduce inequalities in wealth," says Daniels.

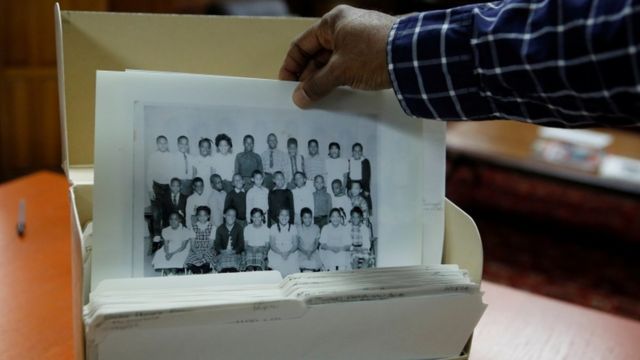

Sixteen black residents whose families have been affected by racist housing policies in place in the city between 1919 and 1969 will benefit

Like other American cities, Evanston has a past of zoning policies and discriminatory housing practices that made it difficult or even impossible for black residents to buy real estate.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, many American cities have taken steps to prevent black residents from moving to certain areas. It was common to include racial restriction clauses in property deeds, establishing that people who were not white could not own or even occupy the place.

Owners in areas where the majority of the population was white also used to refuse to sell property to black buyers. In addition, the black population did not have the same access to housing finance available to white people.

With these and other restrictions, black residents were prevented from acquiring property in the most valued areas and, thus, from accumulating wealth through the ownership of real estate. Decades after the end of these laws, the value of homes in white majority neighborhoods around the country is still higher than in black majority areas.

In Evanston, the report drawn up at the request of the authorities revealed that, despite the 1968 law prohibiting discrimination in the housing sector, until at least the mid-1980s realtors were still trying to get black buyers and tenants to concentrate on majority neighborhoods. black.

The net worth of black families in the United States today represents less than 15% of the net worth of white families. According to census data for 2020, while 74% of white families have their own home, this rate is only 44% among black families.

Reviews

The Evanston program would be a way to repair the damage caused by these discriminatory housing policies, helping to preserve and increase the number of black homeowners and to generate wealth in that community through housing. But the initiative was also criticized.

The proposal was approved by eight votes to one. In justifying her contrary vote, councilwoman Cicely Fleming stressed that she supports the repairs, but not the proposed program, which she described as a "housing plan disguised as repairs".

One of the criticisms is that beneficiaries cannot choose how they want to spend the money, which is distributed in the form of subsidies for investments in housing. Others criticize the small reach, with only 16 families initially contemplated in a universe of 12,000 black residents in the city.

Economist William Darity Jr., a professor at Duke University in North Carolina and co-author of From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century (" From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century") , in free translation), criticizes the use of the term "repairs" in local initiatives such as that of Evanston.

In Evanston, about 16% of the 75,000 inhabitants are black

According to Darity, measures at the local and state level do not constitute a comprehensive and genuine reparations plan, which must have a national scope. In an article in The Washington Post, he said that the use of the term "reparations" can lead to confusion about "the extent of what is needed for genuine restitution".

"This is a good measure for the city to adopt, but let's be clear: it is a voucherprogram for housing, not for repair, and calling it that way does more than help," he said.

Daniels rejects these criticisms and points out that the Evanston program has been certified by Naarc as a model in repairs. He points out that it was the community itself, after several public meetings, that chose the initial focus on housing, and recalls that other sectors will be contemplated over the next ten years.

For Daniels, local initiatives, like Evanston's, do not affect the creation and implementation of a national reparations plan. "One does not exclude the other. On the contrary, they are complementary", he says.

Howard, from N'Cobra, recalls that not only the federal government, but also states and municipalities have been responsible in the past for discriminatory policies that have had a negative impact on the black population. Therefore, the three levels of government should take measures to remedy the damage caused.

"All jurisdictions in this country that have been complicit in crimes against our humanity must be held accountable," says Howard.

Councilor Robin Rue Simmons, author of the proposal in Evanston, described the initiative as "a first step" and noted that the plan alone is not enough and that many programs and more funding are needed until racial injustices can be repaired.

Model

Despite the renewed interest in recent years, the issue of financial reparations to black Americans is still controversial.

Last year's Ipsos survey indicates that only 33% of respondents agree that the government should make cash payments to black people whose ancestors were enslaved. Even among the black population, 20% are against it.

Among the experts who support the idea, there is no consensus on how and how much to pay or how to define who would be entitled. Some propose direct payments in cash, for beneficiaries to use as they wish.

Many cite as an example the reparations paid to victims of the Holocaust by Germany or Japanese Americans illegally sent to concentration camps during the Second World War by the United States.

Darity says that "real" reparations should aim to end the inequality of wealth between the black and white population and estimates that $ 14 trillion (about R $ 79.9 trillion) would be needed, distributed by the federal government in the form of direct payments to every black American descendant of enslaved people in the United States.

After abolition, several laws prevented or made it difficult for black Americans to vote, study, have access to good jobs and finance or acquire property

Others advocate reparations through investments in health, education, employment, housing and other areas with wide disparities. Some cities, such as Asheville, North Carolina, have already approved the creation of commissions to study such measures, which rule out cash payments to beneficiaries.

Other cities and private institutions have also recently announced different repair plans. Last year, California became the first state to sign a law that paves the way for reparations for slavery, mandating the creation of a task force to study and develop proposals on the subject.

Although Evanston's program has received some criticism, experts underscore the importance of a city recognizing its role in discriminatory policies that have hurt the black population and say the initiative can inspire and serve as a model for other governments.

"Each reparation proposal needs to address the (specific) needs of that community," Laura Pitter, deputy director of the United States program for the human rights organization Human Rights Watch, tells BBC News Brasil.

"These needs will vary according to the damage done and what needs to be repaired (in each community), but Evanston's initiative could be a model for others around the country."

Since 1989, the project to create a federal commission to study the legacy of slavery and to make reparation proposals has been presented to Congress every year, but to this day it has never gone ahead. In 2019, for the first time, the Chamber of Representatives (equivalent to the Chamber of Deputies) held a hearing to discuss the topic.

In January this year, the proposal was re-presented by Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee and already has the support of more than 170 congressmen, in addition to the President of the House, Nancy Pelosi, and the leader of the Senate, Chuck Schumer. President Joe Biden himself said, when he was still a candidate, that he would support studies on the subject.

Daniels and other advocates of reparations are optimistic about the increase in support for a national bill and believe that the current scenario is more conducive to such a proposal.

"It is necessary to understand that (the debates about reparations) are not about simply giving each person a check and closing the matter, but about forging a new America," says Daniels. "They are about making this nation face its history, and repair its history."

No comments:

Post a Comment