The Asian city obsessed with cleanliness

Singapore put its cultural legacy of cleanliness to the test during the covid-19 pandemic

I feel it every time I get off the plane: the sudden chill of the air conditioning on full blast and the distinctive aroma of the orchid tea fragrance diffuser.

Airports may all look the same, but landing in Changi — both today and long before the covid-19 pandemic — is a unique Singapore experience.

On the way to Passport Control, walking through the scented air, you'll see impeccably manicured green walls, cleaning crews (in both human and robotic form) and high-tech bathrooms with interactive feedback screens.

If you leave the airport expecting the rest of the city to be so clean and tidy, you won't be disappointed.But cleanliness is more than a merely aesthetic ideal around here.

In this small city-state with just under 56 years of national independence, cleanliness is synonymous with profound social achievements, unprecedented economic growth and, more recently, a coordinated containment of the covid-19 pandemic.

While the population tends to humbly ignore the suggestion that their country is especially clean, its leaders have gone out of their way to obtain and maintain an immaculate public image.

"Singapore's reputation for cleanliness is something the government has consciously sought to promote," explains Donald Low, a Singapore academic who studies public policy.

"Originally, this cleaning had at least two connotations: the first was physical or environmental cleanliness; the second was an honest government and society, which does not tolerate corruption."

Having split from Malaysia in 1965, Singapore, led by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, had big ambitions to become a "first-world oasis in a third-world region," in his words.

"As a newly independent city-state that was eager to attract foreign investment, Lee Kuan Yew rightly believed that these things would set Singapore apart from the rest of Southeast Asia," adds Low.

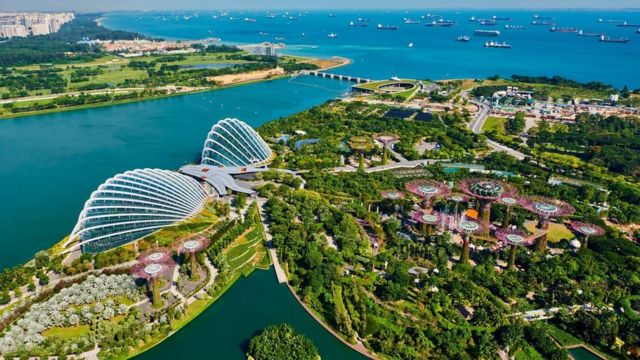

Singapore is known for its impeccable cleanliness and immaculate public image.

In practice, achieving cleanliness meant developing quality sewage systems, creating programs to fight dengue and other diseases, conducting a ten-year project to clean up the Singapore River, planting trees across the island, and relocating street vendors of food, once ubiquitous on the streets, in covered centers dedicated to this.

It also meant carrying out a series of national public hygiene campaigns, calling on Singaporeans to do their part.

"Keeping the community clean requires people aware of their responsibilities," Lee declared at the 1968 launch of Keep Singapore Clean , a now annual anti-waste initiative.

Lee's speech sought to awaken a new sense of national pride among the population, invoking a collective and community spirit that he saw as vital to achieving the nation's goals.

As the city-state's environmental conditions improved, so did Singapore's appeal to foreign investors and tourists, ushering in a long period of unprecedented economic growth.

Today, Singapore regularly leads survey rankings on social conditions, personal safety and quality of life among global cities; while its highly developed market economy is one of the most competitive on the planet.

No place seems more emblematic of the nation's current vigor than the Central Business District, where gleaming office towers and skyscrapers — home to thousands of international business headquarters — share space with world-class luxury hotels, including the iconic Marina Bay Sands designed by Moshe Safdie.

It is the kind of futuristic utopia its then prime minister and founding leader could only have glimpsed in dreams.

Tourists find perfectly paved roads, well-kept public parks and clean streets.

Lee was irritated that, despite his country's achievements, he was somehow always asked about the notorious ban on chewing gum during interviews with foreign media.

He is unlikely to have foreseen the level of global attention this would attract by enacting the law in 1992 to combat spending on cleaning chewed gum from public spaces such as the then-new MRT (public transport) system.

These days, the consumption of chewing gum is actually allowed — if you inadvertently smuggle an open package in your suitcase, you won't end up in jail — but the sale remains prohibited.

Low explains that the infamous gum law is actually quite anomalous in terms of public policymaking in Singapore.

"Instead of outright bans," he explains, "Singapore's government generally uses financial (dis)incentives for activities that generate costs to society," citing as an example the recent introduction of a carbon tax, aimed at reducing emissions and encourage alternative use of clean energy.

But can Singapore really be as clean as its reputation suggests?

Needless to say, the gleaming skyscrapers, boat-shaped hotels and man-made water fountains do not present an accurate picture of everyday life here.

Street food vendors, once ubiquitous on the streets, have been transferred to centers covered with hygiene regulations.

However, even as I left the city center and entered the parts that tourists rarely ventured into, its uniformly designed public housing projects, well-kept public parks, and scrupulously regulated hawker centers were far from grimy.

I went to Geylang, an area of Singapore famous for its excellent local food (praised by Anthony Bourdain) and for being the only legal red light district in the city.

Certainly, I thought, this was where I would see the "real" Singapore.

It was already getting dark and the streets were lit with old-fashioned-looking fluorescent neon signs advertising sex shops, karaoke rooms, and night cafes selling frog leg porridge, a regional delicacy.

"Think of it as Singapore's underworld," said Cai Yinzhou, standing beside me in a dimly lit alley, "the opposite of the manicured skyscrapers we see in the Central Business District."

Yinzhou, a Geylang native who "grew up with sex workers and gambling operators in the neighborhood," now runs Geylang Adventures, an organized tour that aims to "introduce Geylang as a social ecosystem, in addition to the decadent or delicious side that most locals know it".

The Yinzhou tour explores Geylang's brothels, bars and social environment, which often seem to conflict with Singapore's puritanical reputation.

Located at the east end of central Singapore, Geylang is the only legal red light district in the city.

Despite its incongruity within a "family" city, Geylang did not seem a dangerous place. Not far from lawless.

With about 500 security cameras covering the neighborhood, there was a strong sense that its unruly elements—due to drug addiction—were being carefully contained and "often swept away," as Yinzhou described it.

"This is the real Singapore," declared a local man on our tour, "it should be on every tourist's itinerary."

I found myself nodding. Although Geylang did not seem sterile, it came to fit, in its unique way, into Singapore's national narrative of a clean and corruption-free society.

These typical Singapore values were effectively put to the test last year.

Since Lee's fervent campaigns in the late 1960s, the issue of cleanliness has never seemed as pertinent as it does in today's era. In a world that has been radically redefined by the covid-19 pandemic, good public hygiene practices can be a matter of life and death.

On the world stage, Singapore's response to the new coronavirus was widely praised.

Robot dogs transmit recorded messages reminding people to keep a safe distance in public spaces

But unlike most nations, Singapore's handling of the pandemic was not purely reactive.

The country's advanced public hygiene infrastructure meant that, in many ways, Singapore was already prepared.

"We train our agents to deal with the disinfection of infectious diseases even before the covid-19 reaches our land," explained Tai Ji Choong, director of the sanitation department at the National Environment Agency in Singapore.

After planning a course with Singapore Polytechnic School in 2017, Choong told me that the team was "endowed with up-to-date skills and knowledge about disinfection techniques, disinfectant handling, safety procedures and the correct use of personal protective equipment to handle with an outbreak of infectious disease in Singapore".

"Which proved critical when we were notified of the first covid-19 case last year," he added.

This has resulted in the effective implementation of public health technology solutions: mobile apps that allow citizens to purchase face masks; smart technologies to monitor body temperature in large groups; and robot dogs that patrol public parks to enforce social distancing measures.

While effective government management was crucial to dealing with the virus, the pandemic inevitably forced leaders to ask for citizen input.

In Singapore, where wearing masks and tracing contacts is mandatory, the response from the population has been overwhelmingly positive.

But in a society with a cultural legacy of cleanliness, where public hygiene policies and community coordination are the norm, what more could you expect?

No comments:

Post a Comment