Unaccompanied minors: migrants trying to reach the U.S. border

At 17, Michael tries to reach the United States for the first time from his native Honduras

Michael, who is only 17, is making a difficult and dangerous journey: trying to reach the United States of Honduras, his native country.

Accompanied only by his older brother, he says he is exhausted from so much effort. Your feet are full of blisters after days of walking. But his morale is almost intact.

"It is becoming a complicated journey, always running away, through the bush ... but we will arrive. It is worth it because you have to suffer to achieve something," he says, while resting in a shelter for migrants in Palenque, southern Mexico. .

Desperation made Jacqueline, a 19-year-old Honduran woman that we found walking with her 4-year-old son and the rest of her family, to go on the same journey, despite being pregnant.

er a year of 2020 marked by the pandemic and the closing of international borders, thousands of migrants, most of them Central Americans, tried again this year, fleeing poverty and violence in their countries and in search of a better future in the United States.

Alejandro Mayorkas, United States Secretary of Homeland Security, described the situation as "difficult".

"We are on our way to meet more individuals on the southwestern border than in the past 20 years," he said this week.

Most of them are minors, like Michael, traveling without their parents. Hundreds arrive at the border of the United States with Mexico every day.

Families say they have no choice but to make the treacherous journey to the border of the United States.

Many expect the new Biden government's migration policy to be more benevolent with its realities than that followed by former President Donald Trump.

'With hope'

Michael left his home in Yoro, a rural region of northern Honduras, a week ago. He left his mother, his wife and a newborn baby behind.

He crossed Guatemala by bus. But after running out of money, he has been walking non-stop for five days since entering Mexico. He doesn't know how many hours a day he walks. And he had to sell his cell phone to continue his journey.

Michael talks about violence at home. But above all, this young agricultural worker regrets the few opportunities to make a living in Honduras.

"There is nothing. There is no work. There is nothing to be done. So I want to go there [United States] so I can help my family."

Romero saw a dramatic increase in the arrival of migrants since the beginning of the year at his shelter La 72

It is the third time that his brother tries to travel north. But if they reach the border, they plan to split up, with Michael surrendering to the border authorities.

"I was told that if I surrender, they can help me from there. The 'migrate' [as the United States immigration authorities are often called] will ask me if I have relatives there. My aunt can come to me It is the faith that we carry, so that we may be able to cross the border ", he adds, hopeful.

President Joe Biden has suspended the immediate expulsion of migrants under the age of 18 who arrived unaccompanied at the border. Now, they can wait with relatives or foster parents in the United States until their cases are reviewed by the courts.

According to the current American government, Trump's policy, based on a public health order related to the pandemic, was "inhuman" towards minors. However, the order is still in effect to expel families and people over 18.

Michael heard about the changes in Washington. "They told us that the President of the United States would order the removal of all obstacles in our path, that it would be better to cross [the border]. Now that he won, let's hope he helps us," he says, without going into many details.

'Border chaos'

"I think that this foreign policy is not short-term. It will take some time. But [the minors] now arrive with the idea that they can easily enter the United States," says Gabriel Romero, director of the migrant shelter "La 72" in Tenosique, in southern Mexico.

"It is like a vain hope that entry is free, which is not the case."

In February, US border authorities intercepted 9,457 unaccompanied minors, an increase of 60% over January, when 5,858 children were detained.

The dramatic increase in the number of migrants on this route can also be seen in the shelter that Romero commands. In the past few weeks, he has seen long lines of people waiting to come and rest from their trip.

Romero says the restrictions and social distance from the pandemic make it impossible for so many people to be accommodated in their rooms, although he tries to make most of them at least manage to sleep on mattresses on the floor of the complex's chapel.

At night, anyone who is lucky enough to have a cell phone recharges and takes care of it, like a treasure. They know it is the only way to keep in touch with the family.

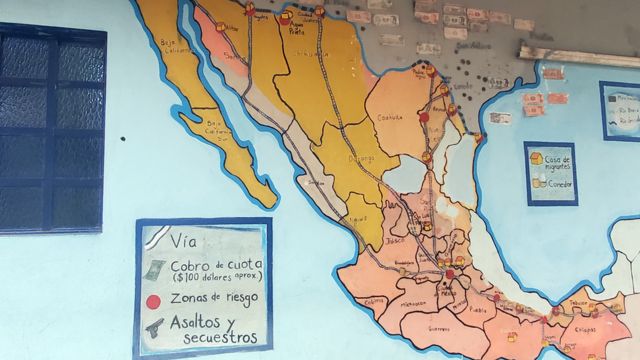

The routes most used by migrants include common points where robberies or even kidnappings occur

Romero says that in 2018 they received a record 15,000 people. In 2020, the pandemic reduced the number to 5,000. But 6,000 have already passed in the first two months of this year alone.

"I am concerned that there will be caravans of larger migrants, of one thousand and two thousand people, and that we may not be prepared for humanitarian attention in these dimensions. (...) If this flow continues in these proportions, we may have chaos at the border," he predicts.

Hurricanes

After the failure of the most recent caravans (the latter was severely dispersed by the Guatemalan army), migrants now prefer to walk in smaller groups.

Just drive for a few hours along your usual routes in southern Mexico to find many of these groups, often with children, walking along roads or train tracks.

Years ago, migrants used to board the train, often referred to as "The Beast", to continue their journey north.

But due to the construction of the Maya Train (one of the favorite projects of the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador), the train has not been running for months.

Biden's new immigration policy ended the immediate expulsion of minors who arrive alone at the border

So they are forced to cross Mexico on foot and the journey is now even longer and more dangerous.

Few residents pay special attention to these migrants. Their faces of tiredness, sometimes of sadness, sometimes of hope, seem to be part of the usual image of these cities.

At a certain point, a vehicle stops in the middle of the road. About eight people, including adults and children, run out of the car, all carrying backpacks. In a matter of seconds, they disappear among the vegetation of the region's jungle.

Migrants say the economic effects of the pandemic have made conditions even worse for them in their countries of origin. In addition, hurricanes Eta and Iota, which hit Central America last year, devastated many communities.

"Our houses collapsed with Eta. We lost everything," says Jacqueline.

"We tried to start over with our business, but they demanded money from us. We were victims of extortion."

The chapel of the Tenosique shelter in Tabasco fills up every night with migrants resting from the harshness of the journey

Jacqueline has already tried to reach the United States. She failed on the first attempt.

Jacqueline's husband Lionel says the risk is worth the possibility of a better life for his family

Danger

Her husband, Lionel, says the money she had to pay because of gang extortion left them with almost nothing, not even enough to buy food.

Without alternatives, the family decided to take a risk on this trip, although they are aware of the dangers lurking along the way.

"We were told that the Zetas are ahead," says Jacqueline, referring to a powerful Mexican gang.

"A man told us that they would cut us to pieces. This is dangerous. You can be kidnapped for ransom," adds Jacqueline.

This is how the feet and shoes of many migrants look after hours of walking

Hours later, after dark, we found Jacqueline and her family again. They are exhausted, hungry. They haven't been able to drink water for hours. They say that on three occasions they saw migratory authorities and had to run and hide among the bushes.

"You have to risk everything. But it is better to risk your life here. In Honduras you can be killed anyway," says Lionel, when asked if his family's life is worth risking on this journey.

Michael walked for hours day and night following the tracks where "The Beast" circulated

Michael still has an entire night to travel to get to the next shelter

"Really. I tell people: why do you think someone would leave your home, your family and your country, to make this trip, if it weren't for sheer necessity"?

Lionel wants to surrender to obtain political asylum when they reach the border. But the US government has insisted this week that it is "evicting most single adults and families".

His family planned to get some rest at night and, hopefully, would arrive in Palenque the next morning.

But no one at the shelter had heard of them two days after our last conversation.

Many migrants spend weeks on the road, sometimes leaving their loved ones behind

'American dream'

Michael resumed his journey the next day. Together with their brother and three Honduran countrymen, they prayed before they started walking. "It gives us the strength to continue. We have faith," he says.

It only takes a few minutes of walking along them to understand the extreme difficulties they will face on this journey.

Jacqueline, in yellow, travels pregnant and with the whole family hoping to be able to enter the United States

They walk on train tracks without proper shoes. The heat is 30 degrees Celsius. They barely have food or drink. They get water from streams by the side of the road or, sometimes, by asking local residents.

"The journey is difficult. We have to run, we fall, we get hurt", he explains.

Although his previous visit to Guatemala was by bus, it was also not easy.

Small groups of migrants are seen continuously on southern Mexico routes

Michael says they were often stopped at police checkpoints, with officers demanding 100 quetzals ($ 13 or $ 73) per person, to allow them to continue. All the groups of migrants we spoke with told us that they are going through the same experience.

As night falls, resting by the road, Michael remains persevering.

"If we give up now, we will get nowhere," he says. The group even makes jokes about how many hours are left to reach the shelter Salto de Agua, their next destination.

He does not regret having started this journey. But it does alert those who may be thinking of doing the same.

"Think carefully, because ... it is difficult. This journey is not for everyone. You need courage and you need to have faith that nothing will happen to you. It is a complicated, extremely complicated path," he says, continuing to walk.

Migrants go through scorching temperatures in the hope of having a better life in the U.S.

Although Michael and his companions expected to arrive at Salto de Agua that night, they did not reach their destination until 8 am.

If nothing stops him, he still has three weeks to go before he reaches the border of the United States and tries to achieve his "American dream".

No comments:

Post a Comment